DURING A VISIT to the Rochester Museum and Science Center in Rochester, New York, in 1991, anthropologist Joanna Cohan Scherer saw three quarter-plate daguerreotypes of Native Americans in the Lewis Henry Morgan Collection (1) that had been tentatively identified as "possibly Plains, 1852," by an unknown cataloguer many years before.

Two of the daguerreotypes were group portraits of seven Indians (cat. nos. 66.132.19 and 66.132.16), they are the subject of this study. Three individuals appear in both images, but the fact that their clothing and accessories are not identical raises the possibility that the daguerreotypes were made on two different occasions. The third daguerreotype in the Morgan collection (66.132.14) depicts a young man holding a rifle and sword, and has no apparent relationship to the other two.

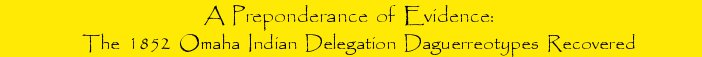

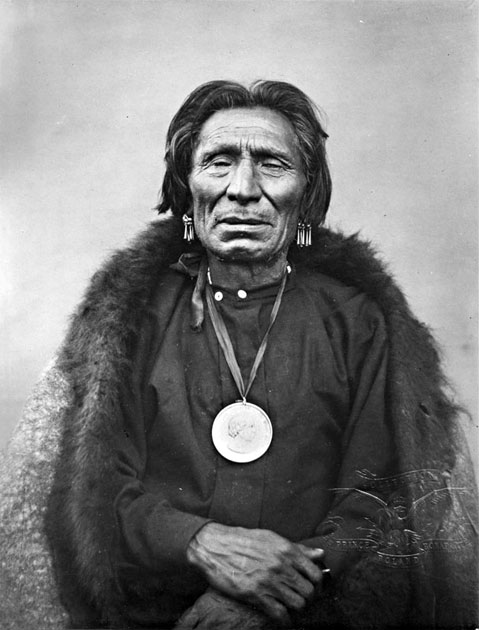

Fig.1 Rochester Museum & Science Center, Rochester, New York, cat. no. 66.132.19

Although Scherer had known about these daguerreotypes in the Morgan Collection, the 1991 visit was the first opportunity for her to examine them in person. On the basis of years studying historical photos, Scherer assumed that these images depicted a delegation to Washington, D.C. Removing the daguerreotypes from their archival containers (they were no longer in their original cases) revealed information that began the process of reconstructing the historical context of the two images.

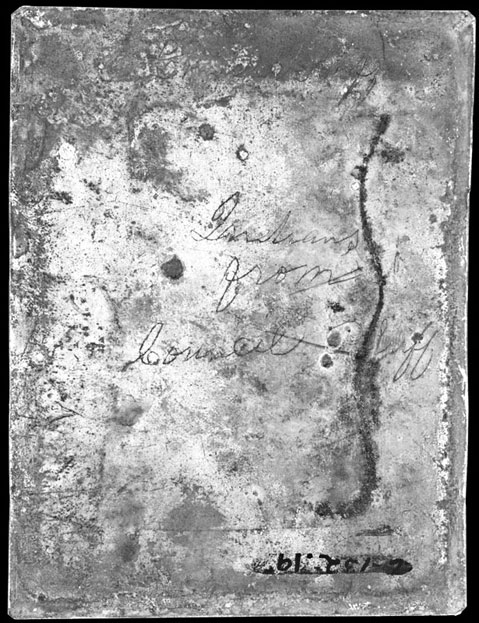

Catalogue number 66.132.19 was a quarter-plate daguerreotype measuring 8 1/2 cm high x 11 cm wide (fig. 1). Scratched on the verso was "Indians from Council Bluff" and above this a badly deteriorated repeat "C...... Bluff" (fig. 2).

Fig.2 Rochester Museum & Science Center, Rochester, New York

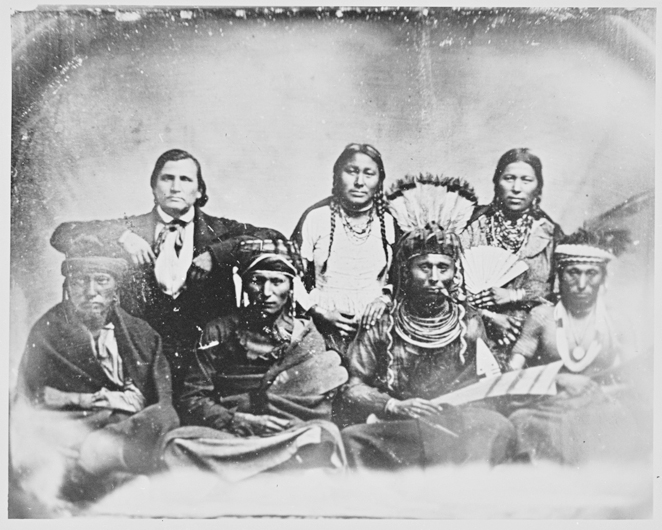

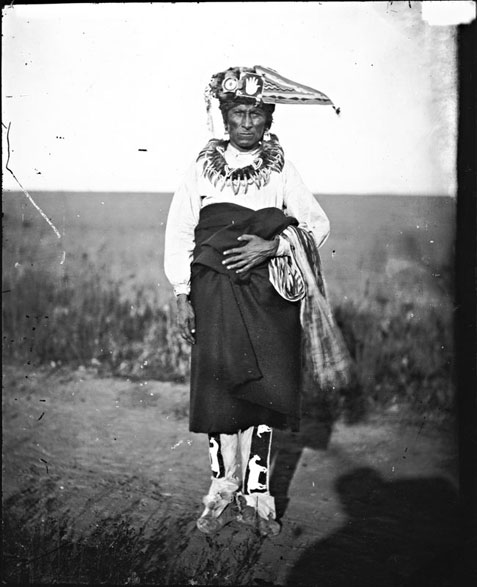

Fig.3 Rochester Museum & Science Center, Rochester, New York, cat. no. 66.132.16

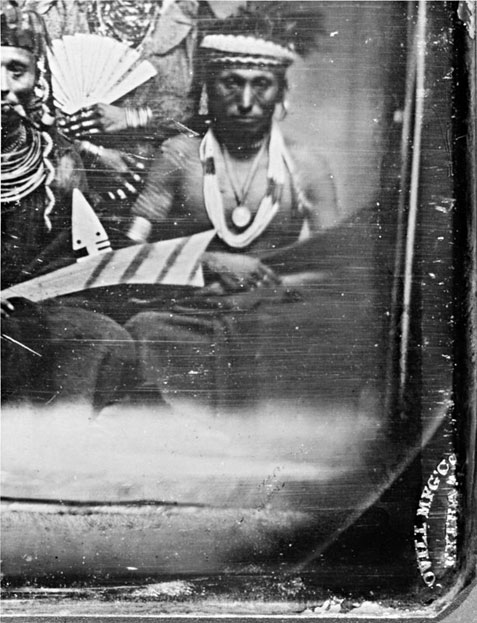

Catalogue number 66.132.16 was a quarter-plate copy daguerreotype measuring 8 1/2 cm high x 11 cm wide (fig. 3). Impressed on the lower right side, recto is "SCOVILL MFG CO. EXTRA" (fig. 4).

Fig.4 Rochester Museum & Science Center, Rochester, New York

The evidence for determining that figure 3 was a copy daguerreotype is the black line (edge of the copper plate) that appears very clearly in figure 4— directly above and to the right of the SCOVILL MFG CO. marking, and that this daguerreotype was much higher in contrast than the other (2). These bits of information allowed the study to proceed.

The silver-plated copper on which figure 3 was copied was manufactured by William H. Scovill and J. M. Lamson. Located in Waterbury, Connecticut, they made daguerreotype plates from 1839-1854 (3). The plates marked "SCOVILLE MFG Co. EXTRA" were manufactured from 1850-1854 (4). Thus it appeared this daguerreotype was copied between 1850 and 1854 or soon afterwards.

The original Council Bluff, the site of Lewis and Clark's 1804 meeting with local Indians, is located on the west side of the Missouri River, north of present Omaha, Nebraska. In the years that followed, the designation Council Bluff or Council Bluffs was used to refer to the entire region from the original site southward to present Bellevue, Nebraska. In 1837 the Council Bluffs Subagency was established at Traders' Point on the east side of the Missouri River near present Council Bluffs, Iowa for the Potawatomi, Ottawa, and Chippewa who had been resettled in the area. The Omaha, Pawnee, Oto, and Missouria were under the jurisdiction of the Council Bluffs Agency itself, located west of the Missouri River at Bellevue. This agency was discontinued in 1854, and a new agency for the Omaha was established in northeastern Nebraska, in present Thurston County (5).

The modern city of Council Bluffs, Iowa, on the Missouri River across from Omaha, was first called Kanesville and was founded by Mormon emigrants in 1847 as a winter way station on their route to Utah. The name was officially changed to Council Bluffs City in 1853, but was known simply as "Council Bluffs, Iowa" well before that time (6). Based on the place name, Scherer hypothesized that the Indians in the daguerreotypes lived in western Iowa or eastern Nebraska. The test would be whether cultural details, clothing, artifacts or identified individuals could verify this deduction.

The "Council Bluff" identification also suggested the possibility that these individuals were of the Council Bluffs band (or United Bands), a group made up of Potawatomi, Chippewa, and Ottawa, who as a result of 1833-1834 Treaty of Chicago had been moved from southern Wisconsin and northern Illinois westward to the prairies of Iowa (7). Several of the individuals in the daguerreotypes wear turbans, which were common headgear for male Potowatomi, Chippewa, and Ottawa during this period. This band, however, signed another treaty in 1846 ceding all their Iowa landholdings and began their migration to a reservation in Kansas. Moreover, additional research, comparing the individuals with other available portraits of men of those tribes, failed to reveal any positive identification.

The focus of the research then shifted from the Council Bluffs band to the Omaha, Pawnee, and Otoe. The Omaha, a tribe speaking a Siouan language, resided near the old Council Bluff Agency at Bellevue between about 1847 and 1855, when they began the move to their new agency. By comparing the daguerreotypes to photographs of Pawnee, Otoe, and Omaha delegates to Washington in the 1860s and 1870s, several of the individuals were identified as Omaha.

Based on the dating of the daguerreotype plates, local newspapers were checked, as well as records in the National Archives and Research Administration. This led to the discovery that an unofficial Omaha delegation left Council Bluffs, Iowa, in September 1851 to visit Washington, D.C. The delegation was sponsored by Joseph Ellis Johnson, Henry W. Miller, and Francis J. Wheeling, all of whom were Mormons (8). The delegation traveled to Washington as two companies, one group with Miller and Wheeling, the other with Johnson (9).

The delegation had two main purposes. The first was to request the federal government's protection from depredations; the Omaha were suffering losses incurred by the Sioux, Pawnee, Kansa, Otoe, and Osage, as well as by the California-bound emigrants trekking through their territory (10). The second was to request assistance in agricultural and associated technologies (11). Both companies of the delegation supported themselves during their travels by putting on performances in various cities.

The delegation traveled overland from Council Bluffs, Iowa, into Illinois and crossed the Mississippi at Rock Island. The journey to Chicago was by wagon and from Chicago by rail (12). The companies were reported in Chicago November 1-6, 1851 (13); in Detroit, but exact dates not known; and in Cleveland, Ohio, November 20-22 (14). The Cleveland Daily Plain Dealer of November 20, 1851 reported that the Omahas, under the leadership of Wheeler, Miller, and Johnson, "will be exhibited this evening at Firemen's Hall. . . [and] will give specimens of their dancing, singing and feats of agility. The Chicago papers represent the scenes in their exhibitions as [of] the wildest and most captivating nature."

Next, the delegation went to Rochester, New York, December 12-13 (15), and were in Syracuse, New York, December 25, 1851 through January 1, 1852 (16). They are also known to have stopped two days in Owego, New York to visit Charles P. Avery (a friend of Johnson), but the exact dates of the visit are not known (17). Exhibitions were presented in Binghamton, New York, January 2, 1852; Susquehanna, Pennsylvania, January 3, 1852; Hancock, New York, January 6, 1852; Port Jervis, New York, January 7-9, 1852; Otisville, New York, January 10, 1852; Middletown, New York, January 11-12, 1852; Albany, New York (the second company), January 12, 1852 (18); Goshen, New York, January 13, 1852; Patterson, New Jersey, January 14, 1852; Passaic, New Jersey, January 15, 1852; and Newark, New Jersey, January 17, 1852 (19).

The Omahas reached Washington on January 21, 1852, met with President Millard Fillmore on February 2, and left for home March 4, 1852. Because they were an unofficial delegation and had come on their own initiative, they had difficulty getting reimbursed for their expenses of "near $8,000" (20). Congress finally appropriated $2,500 to help defray their costs (21).

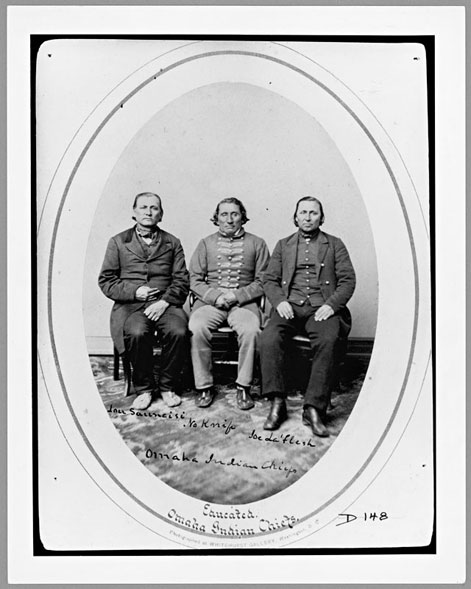

Fig.5 National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution

Several of the eleven individuals in the daguerreotypes have been identified with near certainty by comparison with other existing photographs (22). In fig. 1, front row, second from right is Yellow Smoke, wearing a peace medal and holding his hand palm up (compare with fig. 5).

Fig.6 National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution

In the back row of fig. 1, far left, is Gahíge-ziga ('Chief'), also known as Garner Wood (compare with fig. 6). The men in the back row of fig. 1 wear finger-woven or cloth turbans. The man in the front row, on the far left, wears an upright feather headdress and multiple brass neck rings of a type found in an Omaha archaeological site (23). This is the same man in figure 3, front row, third from left. Note he is wearing two rings on his left hand in the original daguerreotype (fig. 1); the correct orientation in the copy daguerreotype (fig. 3) shows the rings on his right hand.

Fig.7 Nebraska State Historical Society, Lincoln, Nebraska-1394-90

In Figure 3, back row, far to the left, is Louis Sanssoucci or Sansoci, the interpreter (compare with fig. 7). The women are probably two wives of Yellow Smoke (24). The man seated in the front row, far right, with bare chest, has paint or tattooed lines along his arm and chest. He is also in Figure 1, back row, center. His headdress is the same in both images. The different orientations of the feathers of the headdress are understandable because the original daguerreotype (fig. 1) reversed the image while the copy daguerreotype (fig. 3) shows the correct orientation. Also in Figure 3 the man in the front row, far left, is the same man as in Figure 1, back row, far right as yet unidentified. The men wear cloth shirts and have blankets wrapped about themselves.

From reports the delegation is known to have included the following Omaha men (25): Mun-oha-on-a-ba, Two Bears (Machú-naba, Two Grizzly Bears), also known as Yellow Smoke; Gi-he-ga, Great Feaster (Gahíge-ziga, Little 'Chief'), also known as Garner Wood; Tha-thaugh, White Buffalo (Tte-sa); Wash-com-a-ney, Great Traveler (Waska-ma∂i, Hard Walker); Wha-net-wha-ha or Wa-ne-ta-wa-ha, Great Master of all Animals (Wanítta-waxe, Lion); An-gar-ho-?o-ney or Al-go-hom-ony, The Life Guard (Ágaha-ma∂i, Walks Apart); Sha-do-mi-ne, The Tireless Man (Séda-ma∂i); A-da-min-ga (The Fearless Warrior); Ta-da-nig-augh (Mountain Bear); Sha-do-mau-na (One who Dies for a Friend); White Blanket; and Roman Nose.

There were three women: Pa-coo-sa, The White Swan (Ppákka-sa, She Is Pale); Mee-chee-noo-kee, Mountain Dove (26)—or more likely Mígthitonin, Moon Returning, wife of Yellow Smoke (27); and Ta-son-da-bee, Flower of the Plain (Tté-sada-bi, Buffalo that Flashes Lightning).

The interpreter Louis Saun-sa-see (Sanssouci or Sansoci) was a mixed-blood Omaha. According to a letter written by Joseph E. Johnson and J. J. Wheeling to Luke Lea, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, on February 9, 1852 there were nineteen in the delegation; probably the sixteen Omahas (including the interpreter) and Johnson, Wheeling, and Miller. Before reaching Washington, D.C., Miller left the group, and Almon Babbitt took his place (28).

The photographer who took the daguerreotypes is not known for sure. The entry in Joseph E. Johnson's diary for Sunday, February 29, 1852, says: "Glorious! The Sun Shines brightly again—Got two letters from P.O. from Esther & William—took the Indians up for Daguerrah likeness I sat yesterday myself—pictures brot in this Eve." Thus it would appear that daguerreotypes were definitely made in Washington on February 29, but it is unknown if they were the ones that are under consideration here (29).

Another possibility is that Joseph Ellis Johnson, who owned a daguerrean studio in Council Bluffs, Iowa, during the early 1850s, could have had the daguerreotypes taken before the delegates began their trip (30). Or, the daguerreotypes could have been made in Cleveland, Ohio, November 20-22, 1851. The Melodeon Gallery, run by Thomas Paris, advertised its daguerreotype portraiture business (31). The paper also mentioned on November 20, 1851, that the Omaha delegation was to "exhibit at the Melodeon." Perhaps one of the daguerreotypes was made at that time, although it is less likely because the group traveled in two separate companies. The final question which still remains unanswered is who made the copy daguerreotype and why?

The daguerreotypes are portraits of some of the leaders of the Omaha during a difficult period in their history. The Daily National Intelligencer of Washington reported March 2, 1852, on the final interview of the Omahas with Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Lea, held the previous day. The following excerpts give the sense of the posturing, by both federal officials and Indians, that characterized such a visit:

Col. Lea told his red friends that he had sent for them to come and meet him once more before they set out for their distant homes. He was sorry they had been detained in Washington so long . . . When Indians come to Washington, invited by their Great Father, he has every thing arranged beforehand, and then every thing goes on well. But when they come here without his previous notice he is not prepared, and then matters do not go on so well. In their case (the Omahas) the best had been done that the circumstances permitted ... They had by their visit enjoyed a good opportunity to see this vast country, the number and strength of the people, and how great their Great Father is. Their Great Father had many chiefs under him to attend to the different affairs of his children; it was his (Col. Lea's) business to look after the interests of his red children ... You cannot much longer live as you have been living for the past... you must change your manner of living ... Now, your condition must continue to get worse and worse unless you devote yourselves, like whitemen, to cultivate and depend upon the fruits of the earth for subsistence rather than on the results of the chase. This, I am happy to learn, is your wish ... But you ought to know, as men of sense--that all this cannot be done in a day, month or even a year ... Yellow Smoke addressed a few words to the Commissioner in reply, acknowledging how greatly his feelings had been changed for the better, and saying that now he had got all he asked for and all he came to Washington to get...Orders were then given that the Indians be forthwith furnished with suitable apparel... The Indians appear quite reconciled and satisfied, and to have been relieved from the anxiety which of late seems to have pressed upon them.

Johnson's diary for that Monday, March 1, 1852, reads: "Weather pleasant. Visited the Commissioner—and got Medals & Clothing for the Indians & was busy all day—Ind dance—wrote letters & Closing business to leave tomorrow."

Summary

This article describes the research process by which the identity of two previously unidentified daguerreotypes was determined. Textual information survived that daguerreotypes were taken of this delegation, but no images were, until now, so identified.

Photohistorians seem to be primarily interested in either specific photographers or in the photographic process of image-making. Too frequently the ethnographic subject is virtually ignored. Information on the subject can, however, often be extracted from the image when it is treated as a primary historical document. To do so requires a content analysis of the image, using material culture details to help narrow down the people depicted. Then by comparing with other photographs, individual identifications can often be made.

Finally, newspapers and other textual records can help pinpoint the historical context detailing, in this case, the movements of the Omaha delegation and the locations where daguerreotypes might have been made during their travels. It appears that these two daguerreotypes were made on two different occasions, probably by different photographers, but of the same Omaha delegates during their 1851-1852 journey to Washington, D.C. The title "Preponderance of Evidence" was intended to be interpreted literally because in the final analysis Scherer took a leap of faith in "positively" identifying these images as the unofficial Omaha delegation of 1852.

NOTES

1. A daguerreotype is a direct image on silver-plated copper, recognizable by its brilliance and because it cannot be viewed well from every angle. Daguerreotypes, unless corrected, are also reversed left to right. They are often housed in elaborate cases. Popular in the United States from their inception in 1839, daguerreotypes had no competition until 1854, when the ambrotype (a direct image on glass, viewed as a positive when placed against a dark background) was developed. By 1860 the daguerreotype had become outmoded by the wet-plate method of photography, which produced prints on paper and made it easy to duplicate images.

The ethnological collections of Lewis Henry Morgan (1818-1881) are primarily in the Rochester Museum and Science Center, Rochester, New York. Morgan willed his personal collection of archaeological and ethnological objects (including the daguerreotypes), and his library to the University of Rochester along with the residual of his estate. With these came the manuscripts, which were not specifically mentioned in the will. Some of Morgan's ethnological materials were purchased from the estate of Judge Charles P. Avery (d. 1872). Avery and Joseph E. Johnson were known to be good friends (Rufus D. Johnson, J.E.J. Trail to Sundown: Cassadaga to Casa Grande, 1817-1882, The Story of a Pioneer, Joseph Ellis Johnson, Salt Lake City: Joseph Ellis Johnson Family Committee, 166). Evidently Johnson had supplied Avery with Omaha artifacts (Hiram A. Beebe, "Historical Cabinet," The Saint Nicholas: A Monthly Magazine 1(12) Feb.-Mar. 1854:415-416; Printed by Hiram A. Beebe, Owego: Gazette Office). This suggests a possible provenance for these daguerreotypes: from Joseph E. Johnson to Charles P. Avery to Lewis H. Morgan to the Rochester Museum and Science Center via the University of Rochester.

2. Personal communication to author from Roger Watson, International Museum of Photography at the George Eastman House, Rochester, October 30, 1996.

3. Floyd and Marion Rinhart, The American Daguerreotype (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1981), 419.

4. Robert Sobieszek and Odette M. Appel, The Daguerreotypes of Southworth and Hawes (New York: Dover Publications, 1980), 112; and Robert Tart, Photography and the American Scene: A Social History 1839-1889. (New York: MacMillan, 1938 [reprinted 1964, Dover Publications]. 54-55).

5. Data furnished by Richard E. Jensen, Nebraska State Historical Society, May 1997.

6. Charles H. Babbitt, Early Days at Council Bluffs (Washington: Press of Byron S. Adams, 1916).

7. James A. Clifton, "Potawatomi" in Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 15. Northeast Bruce Trigger, ed. (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1978), 725-742.

8. Johnson, J.E.J. Trail to Sundown, 156-173.

10. Daily National Intelligencer, Washington, D.C. February 4, 1852.

11. The Daily American, Rochester, New York, December 12, 1851.

12. Johnson, J.E.J. Trail to Sundown, 156-162.

13. Chicago Daily Democrat, Chicago, Illinois, November 1-6, 1851.

14. Daily Plain Dealer, Cleveland, Ohio, November 20-22, 1851.

15. The Daily American, Rochester, New York, December 12-13, 1851.

16. Syracuse Daily Standard, December 31, 1851.

17. Beebe: 1854, 413-416. See also Johnson, J.E.J. Trail to Sundown, 166, 168. For Avery's possible connection to the provenance of the daguerreotypes, see note 1.

18. Johnson, J.E.J. Trail to Sundown, 172.

19. Joseph Ellis Johnson, 1852. [Diary] (Manuscript. 110, Box 1-A, Folder 2 in Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City).

"Abstract of Expenses of the 0-Ma-Ha Indian delegation now in Washington conducted and in part paid by F.J. Wheeling and J.E. Johnson. Company consisting of nineteen. Expense of transportation from Council Bluffs to Washington $775.80; Four months victualling on the way $2355.75; Blankets, clothing and various necessary articles $351.65; Medicine, medical attendance, etc. $251.50; One months board in Washington $1200; Paid Interpreter for time and service $400; Six months service of Wheeling and Johnson $1200; Amount required to return home $1425. Total: $7959.70". Letter from F.J. Wheeling and J.E. Johnson to the Bureau of Indian Affairs on the Omahas visit, February 9, 1852. (Letters Received by the Office of Indian Affairs 1824-1881 from the Council Bluffs Agency. Microfilm publication 234, roll #218, Record Group 75, Bureau of Indian Affairs, National Archives, Washington).

21. U.S. Congress, 1852 Estimates for an Appropriation to Defray the Expense of a Party of Omaha Indians. H. Exec. DOC. 76, (32nd Congress, 1st session 1852) 3.

22. Photographs used in identification of individuals:

23. John M. O'Shea and John Ludwickson, Archaeology and Ethnohistory of the Omaha Indians: The Big Village Site. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1992).

24. According to the Daily National Intelligencer, Washington, January 30, 1852, the principal chief "Mon-choo-ne-ba is accompanied here by two of his five wives." December 12, 1851, The Daily American noted "The Head Chief has with him two of his wives, exceedingly pretty squaws seventeen and fifteen years of age."

25. Format of names: Original Omaha spellings from Johnson (1961:159) and The Daily American December 12, 1851; then original translations; and finally current spelling of Omaha names and translation if different from the original. The current Omaha spelling and English translation is based on personal communication with John E. Koontz, University of Colorado, Linguistics Department, August 1992.

26. Per Johnson, J.E.J. Trail to Sundown, 159 and 169.

27. Fletcher, Alice C. and La Flesche, Francis, "The Omaha Tribe" in 27th Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology for 1905-1906 (Washington, 1911; reprinted: Johnson Reprint Corporation, New York, 1970.), plate 26; 153; 185.

28. Johnson, J.E.J. Trail to Sundown, 174.

29. There was no city directory for Washington, D.C. in 1852. The following listing of daguerreans and galleries are from advertisements and the city directory of 1853: Nahum S. Bennett, John Hawley Clarke, James A. Cutting, Augustus and William McCarty, Odeon Daguerrean Rooms, Blanchard P. Paige, Plumbe National Daguerrian Gallery, Marcus Aurelius Root, Roots National Daguerreotype Gallery, Root & Clark (Clarke), Root & Co. (M.A. Root & John H. Clarke), Madge(?) Talmage, E.C. Thompson, Thompson's Skylight Daguerrean Gallery, Julian Vannerson, Charles H. Venable, Jesse H. Whitehurst and the Whitehurst's Daguerrean Gallery. Information from notes supplied by Paula Fleming.

30. From advertisements in the Frontier Guardian (1849-1852) the known daguerreans in Council Bluffs, Iowa, were: Smith, from 1852; Chaffin, from April 1851; and Johnson, who advertised as "[h]aving employed an able artist in the... business" of "Daguerrean likenesses," beginning on April 18, 1851 and also "New Rooms" from 1852.

31. Daily Plain Dealer, Cleveland, Ohio November 19, 1851.

[ TOP ]