- Benedicte Wrensted ›

- Indian Photographs

Indian Photographs

Amelia Frost and the Presbyterian Mission

Amelia Frost (b. 1850) arrived at the Fort Hall Indian Reservation in July, 1887, from Albion, New York, where she had attended the Phipps Union seminary. She was sent by the Connecticut Indian Association. In 1892, Agent Fisher reported that Miss Frost was:

universally liked and respected by both Indians and the whites. She has worked faithfully in the discharge of her duties, not only to Christianize the Indian, but to assist and comfort the sick and needy, besides giving a home, including clothing and education to several little Indian girls.

In 1901 Amelia Frost built a new church and mission quarters on 160 acres of land granted 8 miles north of the agency. She left the mission in 1906 to return east, and died in 1926.

Amelia Frost was instrumental in bringing families from Fort Hall and Pocatello closer together. She corresponded with and knew the Cook/Leonard family from at least the early 1890s. She probably knew Mrs. Leonard Derr through her sister Mrs. A. L. Cook.

A letter from Mrs. Derr to E. O. Leonard, November 5, 1899, said:

"Miss Frost was down Friday. She brought for you the enclosed Indian pictures. I sent one of yours to them. She said they would be so pleased."

Exchange of photos between individuals and families from both communities underscores the warm ties that existed, but are now too often forgotten.

Credit: * National Archives and Records Administration, Still Picture Branch: 75-SEI-92

Credit: Smithsonian Institution, National Anthropological Archives, Eugene O. Leonard Collection, Photo Lot 92-3.

Credit: Smithsonian Institution, National Anthropological Archives, Eugene O. Leonard Collection, Photo Lot 92-3.

Tetoby frequently accompanied Miss Frost on church business. Leonard correspondence mentions his missionary visits to southern Utah (November 24, 1900), and to various localities in Idaho (May 3, 1905). The Pocatello Tribune (December 21, 1907) notes his visit to the Umatilla and Nez Perce Reservations.

In a letter to E. O. Leonard October 4, 1903, Hubert wrote:

"My heart is always so glad when my dear Christian brother Eugene prays with us." The original print of this photograph is inscribed on the back: "To my friend Eugene Leonard, Hubert Tetoby 1900."

Credit: Smithsonian Institution, National Anthropological Archives, Eugene O. Leonard Collection, Photo Lot 92-3.

The Georges were actively involved in the Presbyterian Church. While the Fort Hall mission building was under construction (1900-1901), Miss Frost lived with the Georges. Billy George was also one of the reservation residents who forged and strengthened ties between the Fort Hall and the Nez Perce Reservations.

According to Willie George, his parents fought with Buffalo Horn in the Bannock War of 1878. The war was triggered by destruction of the staple food camas bulbs on the Camas Prairie. The rebellion ended after a summer of "fox-and-hounds" chases in Oregon, Idaho and Montana. It was the Sho-Bans' last armed battle.

Billy George served as a policeman on the reservation, thus his nickname, "Captain." In 1882, a police force had been established by Indian agent A. L. Cook. In 1888 a police court was also established. By 1890, the court had three judges - one Bannock and two Shoshone, one of whom was Billy George. For a salary of $8.00 per month, Billy George presided that year over approximately 50 cases involving such issues as boundary disputes and marital problems.

Pat Tyhee

"Before and after" photographs were commonly used by missionaries, Indian agents and government officials to document their success in teaching native peoples. The photographs promoted a political agenda that may or may not have been based on fact.

Pat L. Tyhee (b. 1853 d. 1924), the son of Bannock Chief Tyhee, was one of the most photographed Indians of Fort Hall. Images of him date from 1884 to 1924.

Credit: * National Archives and Records Administration, Still Picture Branch: 75-SEI-26.

Credit: Smithsonian Institution, National Anthropological Archives, Eugene O. Leonard Collection, Photo Lot 92-3.

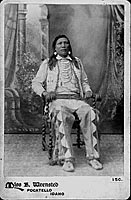

Here Tyhee is wearing a cloth shirt, a multi-strand clam shell necklace, and shell earrings, a metal-studded belt, moccasins and leggings beaded in characteristic Shoshone geometric design.

Credit: Smithsonian Institution, National Anthropological Archives, Eugene O. Leonard Collection, Photo Lot 92-3.

Even though Pat Tyhee no doubt visited the Wrensted studio on his own to have these pictures taken they are reminders of official policy aimed at Indian acculturation. There was a concerted effort by Indian agents to pressure men to cut their hair and wear non-Indian clothes.

According to The Pocatello Tribune, May 1901,

Agent A. F. Caldwell announced that the Indian Department had generously provided a number of new farm wagons for those interested in farming, but no Indian would receive one until he agreed to a haircut. . .as Indians lined up, two barbers spent an entire day cutting the long braids of Indian farmers, who reluctantly submitted to the 'civilizing' ordeal to get some wheels.

Credit: * Idaho Museum of Natural History, Ruffner Collection: 253159

Tyhee looks older in the photo with Theodore Turner than in either of the photos shown here. Comparing these images alerted the researcher that a greater span than Wrensted's 17 years was reflected, and that another photographer's work was present in the IMNH collection.

Mary Garvey, Wrensted's successor, took a series of photographs of Pat Tyhee in headdress between 1912 and 1918. These have frequently been used in publications and displays. By 1912 Tyhee was an elder and could dress in warbonnet and regalia, although doing so was reserved for ceremonial occasions. By then, the stereotype of the Plains Indian was fully in place, influencing the style of items worn.

Credit: * Idaho Museum of Natural History, Ruffner Collection: 253151.

Associated with the Christian missionary community, Tyhee was described by The Pocatello Tribune in 1904 as one of the most "progressive" Indians on the Fort Hall Reservation. He was chosen by Agent Major Caldwell to be one of the four representatives of the tribes at the Presidential inauguration of William Howard Taft in Washington, DC, in 1909.

At the same time, Tyhee was very influential among the Indians of Fort Hall. He never ceased being a spokesman for his people, and served as a chief judge of the Indian court.

The Edmo Family

The Edmos were one of the prominent families on the Fort Hall Indian Reservation. They were descended from Arimo (b. about 1806 d. 1896), a leader of the Northern Shoshone, who had seven sons and one daughter. The name Arimo was anglicized to "Edmo." Of the 191 known Wrensted Native American photographs, 17 (9%) are of the Edmos.

Credit: Idaho Museum of Natural History, Pocatello. 253227.

Jack Edmo (b. 1863 d. 1929) was the next to youngest of Arimo's seven sons. It is Jack and his family whose images we find again and again in Wrensted's work. Edward Edmo Sr., Jack's nephew, a nationally known Shoshone-Bannock storyteller, describes his uncle as a man who liked to dress up, to participate in powwows and Fourth of July festivities, and to be "in front of the camera."

Credit: * National Archives and Records Administration: Still Picture Branch, Record Group 75-SEI-65

Eugene and Leonard were Jack and Lizzie Edmo's two oldest sons. They were named after Eugene O. Leonard, the only son of Mrs. Leonard Derr. E. O. Leonard came to Pocatello in the 1890s and lived with his mother's sister, Mrs. A. L. Cook. The names attest to the close association of the Cook/Leonard family with the Edmos. Both Eugene and Leonard Edmo became well-known in rodeos.

Jack is wearing fringed leggings and bead hair ornaments. He also wears a fur sash with mirrors and a beaded vest with an American flag design, which according to Edward Edmo, Sr., were probably received as gifts from the Sioux. Jack Edmo's family seems to have adopted the flag design, since it appears as decoration on various vests and moccasins.

Jack and his wife Lizzie often traveled to other Indian reservations. During such visits they accumulated many presents of clothing and accessories, which they wore with pride. Wrensted's photo record corroborates this oral history.

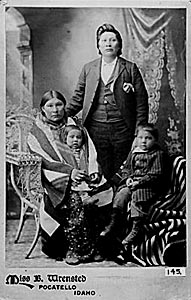

Jack and Lizzie Randall Edmo's children: left to right, Bessie (b. 1892 d. 1984), Eugene, Helen (b. 1888). This photograph was taken in 1898. Helen was the oldest of Jack's children; she died during childhood.

Bessie wears a traditional cut - cloth dress, beaded leggings and moccasins. Helen wears a dress decorated on the bodice with cowrie shells and faceted beads. Her long necklace is a Plains women's style.

Credit: Smithsonian Institution, National Anthropological Archives, Eugene O. Leonard Collection, Photo Lot 92-3.

Credit: * National Archives and Records Administration: Still Picture Branch, Record Group 75-SEI-76.

Credit: Smithsonian Institution, National Anthropological Archives, Eugene O. Leonard Collection, Photo Lot 92-3.

Credit: * National Archives and Records Administration: Still Picture Branch, Record Group 75-SEI-17.

One of the existing copies of this image is a postcard with "Pocatello Idaho" handwritten on the front. Photographic postcards were widespread by the early years of the twentieth century. It is probable that the Wrensted studio followed general trends, turning photographs of the local Indians into postcards.

However, since Benedicte did not copyright these images, she apparently was not using them in a major commercial business. The Pocatello Tribune reported in an article on the 1910 Fourth of July Festivities that photos of Sho-Ban taken four years earlier were "printed on postcards and sent all over the world." Perhaps this is one of those images.

[ TOP ]