- Benedicte Wrensted ›

- Reading Historical Photos

Reading Historical Photos

Glass Negatives and the Effects of Retouching

One of the characteristics of Benedicte Wrensted's work was her retouching of negatives. Rather than presenting her subjects with imperfections, she brushed their faces and hands to erase shadows, blemishes, or signs of aging, thus assuring customer satisfaction.

The practice of retouching was not uncommon in Wrensted's day. But her distinctive style of varnishing in a circular pattern helped establish that a number of unattributed negatives in the collection at the Idaho Museum of Natural History were hers.

Johnny Ballard was born in Wyoming, June 29, 1876, four days after the Battle of the Little Big Horn. When his father Jim Ballard died, Johnny Ballard became the last hereditary leader of the Bannock. He spoke numerous languages, including Sioux, Crow, and Cree. He married Julia Baker in a ceremony at the Mission of Good Shepherd on the Fort Hall Reservation.

Little is known about Charlie Pizoka. His vest is of old Sioux style, possibly from South Dakota.

Frank Randall was born January 1, 1872, to Cayuse Mary (Bannock) and George Randall (Anglo-American). Frank Randall was elected councilman for the Ross Fork District in 1930 and served on the tribes' Advisory Council before the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act. He was outspoken on the issues of alcoholism and better education for Native Americans. He was photographed often throughout his life, by Wrensted and others.

Johnny Ballard (left; b. 1876 d. 1948) and Charlie Pizoka (right; b.1867 d. 1930) posed for this Wrensted photograph between 1895 and 1912. The image has not been retouched, and shows lines in both men's faces.

The men wear beaded moccasins, vests and leggings, and cloth shirts. Ballard's hair is in long, fur-wrapped braids, a style common among the Bannock and Northern Shoshone. Bone or glass bead chokers, multi-strand necklaces, loom-beaded arm bands, metal-studded belts and metal bracelets were also commonly worn.

Both Ballard and Pizoka have upright, Blackfeet-style feather headdresses. Ballard holds a catlinite trade pipe and a gun while Pizoka holds a feathered staff.

Credit: * National Archives and Records Administration, Still Picture Branch: 75-SEI-99.

Johnny Ballard (left) and Charlie Pizoka (right) pose again for Wrensted, this time with Frank Randall (seated). The photograph clearly shows retouching. Although the two photos were taken on the same day, Pizoka and Ballard appear much younger in the retouched image.

Frank Randall is wearing leggings with beaded cuffs and a bandolier with hoof tinklers. His earrings are shell "moons." The shell is probably from a West Indian conch, and was a popular trade item throughout the nineteenth century. Because Frank Randall's left hand was disfigured, he always covered it with a piece of fur or blanket. This habit earned him the Indian name "Bear Paw," which translates literally as "Fur on His Hands" or "Holding Fur."

Credit: * National Archives and Records Administration, Still Picture Branch: 75-SEI-66.

Credit: Scherer Personal Collection.

Credit: Scherer Personal Collection.

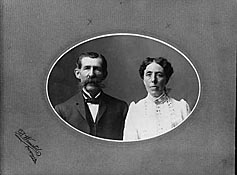

Contrasting Depictions

One of the major differences between Wrensted's portraits of Euro-American and Sho-Ban patrons is the partial versus full-length pose. In her Euro-American portraits, the focus is on the subject's face, showing only the head and shoulders, with the image often presented in an oval frame. These partial body poses are probably photographic emulations of the painted miniature, part of European portraiture tradition.

Credit: Smithsonian Institution, National Anthropological Archives, Eugene O. Leonard Collection, Photo Lot 92-3.

Credit: * National Archives and Records Administration, Still Picture Branch: 75-SEI-28.

In contrast, Wrensted's photos of Indians were usually full-length, which de-emphasized faces, but documented the elaborate clothing. Was this a preference of the photographer or the subject? It is probable that the Sho-Ban selected the pose, as most patrons of photographic studios made their choices from displayed examples.

Credit: Smithsonian Institution, National Anthropological Archives, Eugene O. Leonard Collection, Photo Lot 92-3.

Credit: * National Archives and Records Administration, Still Picture Branch: 75-SEI-13.

Credit: Scherer Personal Collection.

Credit: Scherer Personal Collection.

A Sho-Ban preference for whole images would be consistent with the Native American lack of a facial portraiture tradition. In Indian rock art as well as nineteenth-century Indian ledger art, human figures were full length.

Credit: * Idaho Museum of Natural History, Ruffner Collection: 253274.

[ TOP ]